Sir James Clark Ross on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British

Ross participated in John's unsuccessful first Arctic voyage in search of a

Ross participated in John's unsuccessful first Arctic voyage in search of a

On 8 April 1839, Ross was given orders to command an expedition to Antarctica for the purposes of 'magnetic research and geographical discovery'. Between September 1839 and September 1843, Ross commanded on his own Antarctic expedition and charted much of the continent's coastline. Captain Francis Crozier was second-in-command of the expedition, commanding , with senior lieutenant Archibald McMurdo. Support for the expedition had been arranged by Francis Beaufort, hydrographer of the Navy and a member of several scientific societies. On the expedition was gunner Thomas Abernethy and

On 8 April 1839, Ross was given orders to command an expedition to Antarctica for the purposes of 'magnetic research and geographical discovery'. Between September 1839 and September 1843, Ross commanded on his own Antarctic expedition and charted much of the continent's coastline. Captain Francis Crozier was second-in-command of the expedition, commanding , with senior lieutenant Archibald McMurdo. Support for the expedition had been arranged by Francis Beaufort, hydrographer of the Navy and a member of several scientific societies. On the expedition was gunner Thomas Abernethy and

On 31 January 1848, Ross was sent on one of three expeditions to find John Franklin. Franklin's second in command was Ross's close friend Francis Crozier. The other expeditions sent to find Franklin were the Rae–Richardson Arctic expedition and the expedition aboard HMS ''Plover'' and through the Bering Strait. He was given command of , accompanied by . Because of heavy ice in Baffin Bay he only reached the northeast tip of Somerset Island where he was frozen in at

On 31 January 1848, Ross was sent on one of three expeditions to find John Franklin. Franklin's second in command was Ross's close friend Francis Crozier. The other expeditions sent to find Franklin were the Rae–Richardson Arctic expedition and the expedition aboard HMS ''Plover'' and through the Bering Strait. He was given command of , accompanied by . Because of heavy ice in Baffin Bay he only reached the northeast tip of Somerset Island where he was frozen in at

Ross married Ann Coulman in 1843. A blue plaque marks Ross's home in Eliot Place,

Ross married Ann Coulman in 1843. A blue plaque marks Ross's home in Eliot Place,

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, N ...

, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was an Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Pass ...

, and, in particular, for his own Antarctic expedition from 1839 to 1843.

Biography

Early life

Ross was born in London, the son of George Ross and nephew of John Ross, under whom he entered theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

on 5 April 1812. Ross was an active participant in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, being present at an action where HMS ''Briseis'', commanded by his uncle, captured ''Le Petit Poucet'' (a French privateer) on 9 October 1812. Ross then served successively with his uncle on HMS ''Actaeon'' and HMS ''Driver''.

Arctic exploration

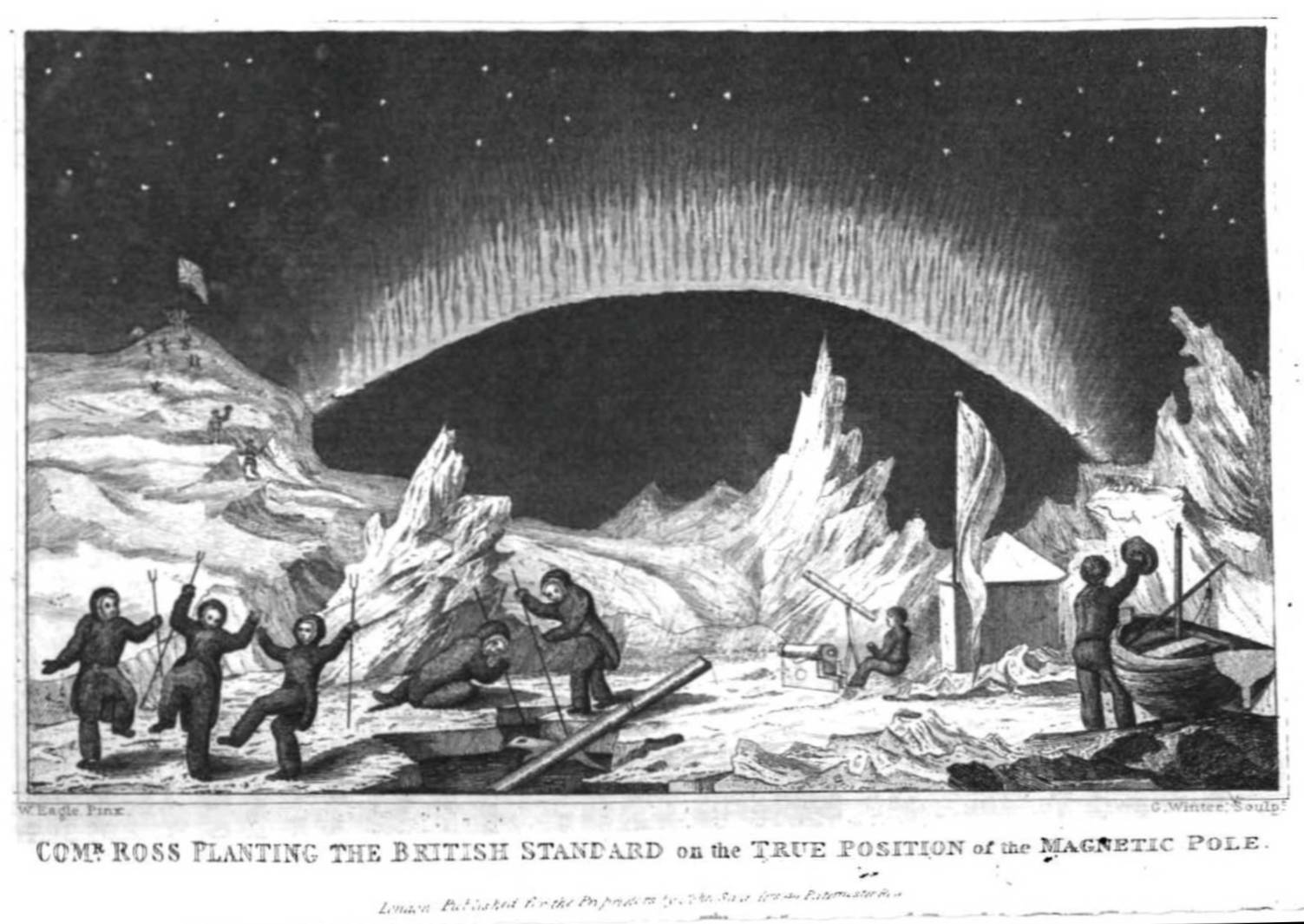

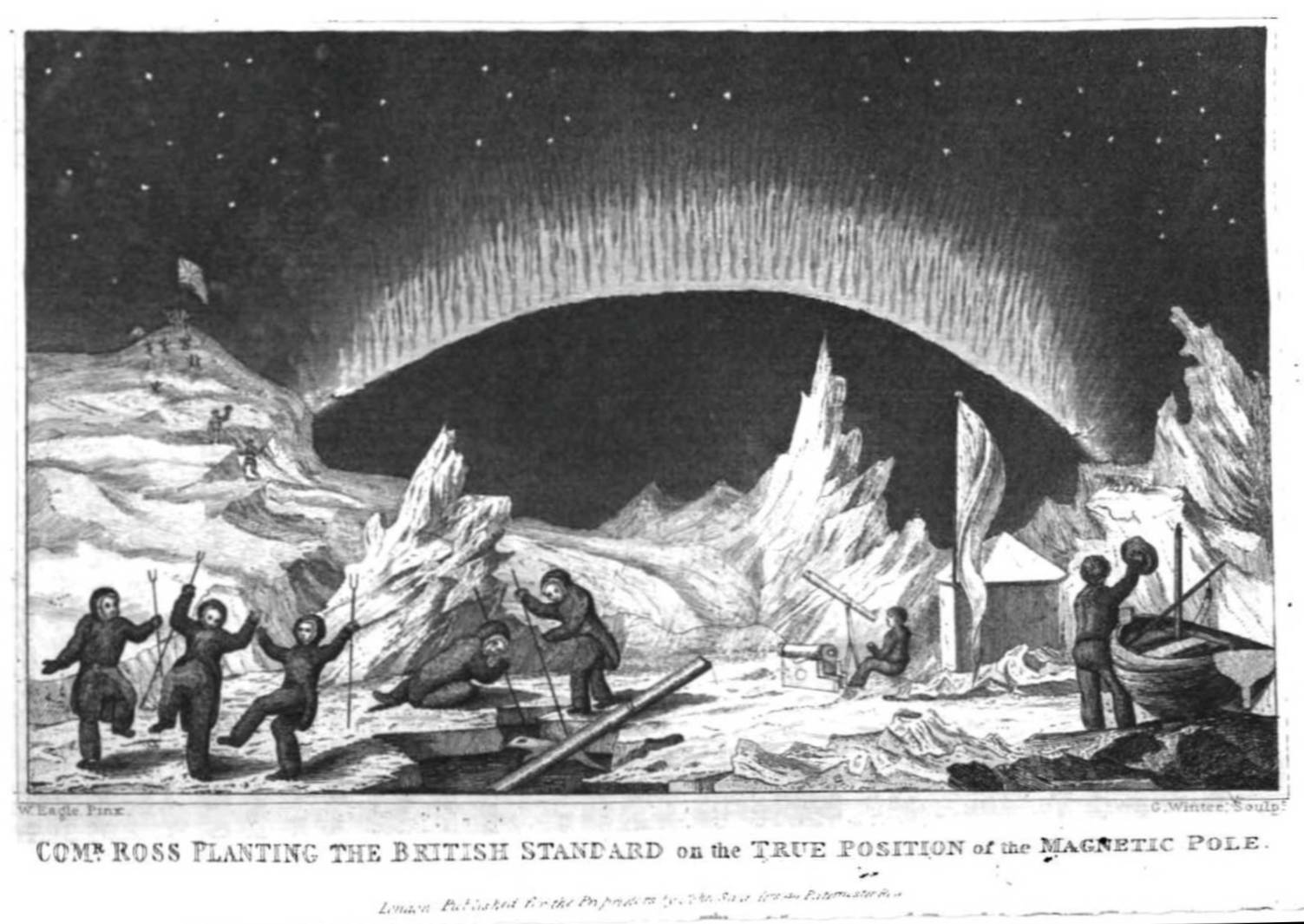

Ross participated in John's unsuccessful first Arctic voyage in search of a

Ross participated in John's unsuccessful first Arctic voyage in search of a Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arc ...

in 1818 aboard ''Isabella''. Between 1819 and 1827 Ross took part in four Arctic expeditions under William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was an Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Pass ...

, taking particular interest in magnetism and natural history. This was also where he served as midshipman with Francis Crozier

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier (17 October 1796 – disappeared 26 April 1848) was an Irish officer of the Royal Navy and polar explorer who participated in six expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic. In May 1845, he was second-in-comman ...

, who would later become his close friend and second-in-command. From 1829 to 1833 Ross again served under his uncle on John's second Arctic voyage. It was during this trip that a small party led by James Ross (including Thomas Abernethy) located the position of the north magnetic pole

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic compass needle is allowed t ...

on 1 June 1831, on the Boothia Peninsula

Boothia Peninsula (; formerly ''Boothia Felix'', Inuktitut ''Kingngailap Nunanga'') is a large peninsula in Nunavut's northern Canadian Arctic, south of Somerset Island. The northern part, Murchison Promontory, is the northernmost point of ...

in the far north of Canada, and James Ross personally planted the British flag at the pole. It was on this trip, too, that Ross charted the Beaufort Islands, later renamed Clarence Islands

The Clarence Islands are a Canadian Arctic island group in the Nunavut Territory. The islands lie in the James Ross Strait, east of Cape Felix, off the northeast coast of King William Island. They are about west of Kent Bay on the Boothia Pe ...

by his uncle. Ross then served as supernumerary-commander of HMS ''Victory'' in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

for 12 months.

On 28 October 1834 Ross was promoted to captain. In December 1835 he offered his services to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

to resupply 11 whaling ship

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

s which had become trapped in Baffin Bay. They accepted his offer, and he set sail in HMS ''Cove'' in January 1836. The crossing was difficult, and by the time he had reached the last known position of the whalers in June, all but one had managed to return home. Ross found no trace of this last vessel, ''William Torr'', which was probably crushed in the ice in December 1835. He returned to Hull in September 1836 with all his crew in good health.

British Magnetic Survey

From 1835 to 1839, except for his voyage with ''Cove,'' he was one of the principal participants in the British Magnetic Survey, a magnetic survey ofGreat Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

, with Edward Sabine

Sir Edward Sabine ( ; 14 October 1788 – 26 June 1883) was an Irish astronomer, geophysicist, ornithologist, explorer, soldier and the 30th president of the Royal Society.

He led the effort to establish a system of magnetic observatories in ...

, John Phillips and Humphrey Lloyd. This also included some work on geomagnetic

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic ...

measurements in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

in 1834–1835, working with Sabine and Lloyd. In 1837, Ross assisted in T. C. Robinson's improvement of the dip circle {{Refimprove, date=November 2011

Dip circles (also ''dip needles'') are used to measure the angle between the horizon and the Earth's magnetic field (the dip angle). They were used in surveying, mining and prospecting as well as for the demonst ...

during the survey; anomalous results had been discovered by Ross in 1835 in Westbourne Green. In 1838, Ross completed magnetic observations at 12 different stations throughout Ireland. The survey was completed in 1938; some supplementary measurements by Robert Were Fox were also used.

Antarctic exploration

On 8 April 1839, Ross was given orders to command an expedition to Antarctica for the purposes of 'magnetic research and geographical discovery'. Between September 1839 and September 1843, Ross commanded on his own Antarctic expedition and charted much of the continent's coastline. Captain Francis Crozier was second-in-command of the expedition, commanding , with senior lieutenant Archibald McMurdo. Support for the expedition had been arranged by Francis Beaufort, hydrographer of the Navy and a member of several scientific societies. On the expedition was gunner Thomas Abernethy and

On 8 April 1839, Ross was given orders to command an expedition to Antarctica for the purposes of 'magnetic research and geographical discovery'. Between September 1839 and September 1843, Ross commanded on his own Antarctic expedition and charted much of the continent's coastline. Captain Francis Crozier was second-in-command of the expedition, commanding , with senior lieutenant Archibald McMurdo. Support for the expedition had been arranged by Francis Beaufort, hydrographer of the Navy and a member of several scientific societies. On the expedition was gunner Thomas Abernethy and ship's surgeon

A naval surgeon, or less commonly ship's doctor, is the person responsible for the health of the ship's company aboard a warship. The term appears often in reference to Royal Navy's medical personnel during the Age of Sail.

Ancient uses

Special ...

Robert McCormick, as well as Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of ...

, who had been invited along as assistant ship's surgeon. ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' were bomb vessel

A bomb vessel, bomb ship, bomb ketch, or simply bomb was a type of wooden sailing naval ship. Its primary armament was not cannons (long guns or carronades) – although bomb vessels carried a few cannons for self-defence – but mortars mounted ...

s—an unusual type of warship named after the mortar bombs they were designed to fire and constructed with extremely strong hulls, to withstand the recoil of the heavy weapons. The ships were selected for the Antarctic mission as being able to resist thick ice, as proved true in practice.

En route to the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

, Ross established magnetic measurement stations in Saint Helena, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, and Kerguelen

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the sub-Antarctic constituting one of the two exposed parts of the Kerguelen Plateau, a large ...

before arriving in Hobart in early 1840 and establishing a further permanent station with the help of governor John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through t ...

before waiting for summer.

Ross crossed the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. So ...

on 1 January 1841. Shortly after, he discovered the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

and Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. I ...

, charting of new coastline, reaching Possession Island on 12 January and Franklin Island on 27 January (which Ross named after John Franklin). He then reached Ross Island, with the volcanoes Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a summ ...

and Mount Terror, which were named for the expedition's vessels. They sailed for along the edge of the low, flat-topped ice shelf they called variously the Barrier or the Great Ice Barrier, later named the Ross Ice Shelf in his honour.

After being forced to overwinter in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, Ross returned to the Ross Sea in December 1841 before travelling east past Marie Byrd Land to the Antarctic Peninsula. The next winter, the expedition overwintered in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

before returning to survey the Antarctic Peninsula over the summer of 1842–1843. Ross attempted to penetrate south at about 55° W, and explored the eastern side of what is now known as James Ross Island

James Ross Island is a large island off the southeast side and near the northeastern extremity of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which it is separated by Prince Gustav Channel. Rising to , it is irregularly shaped and extends in a north–south ...

, discovering and naming Snow Hill Island

Snow Hill Island is an almost completely snowcapped island, long and wide, lying off the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. It is separated from James Ross Island to the north-east by Admiralty Sound and from Seymour Island to the north ...

and Seymour Island

Seymour Island or Marambio Island, is an island in the chain of 16 major islands around the tip of the Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula. Graham Land is the closest part of Antarctica to South America. It lies within the section of the isla ...

. Ross reported that Admiralty Sound appeared to him to have been blocked by glaciers at its southern end.

The expedition's main aim was to find the position of the south magnetic pole. While Ross failed to reach the pole, he was able to determine its location. The expedition also produced the first accurate magnetic maps of the Antarctic.

Ross's ships arrived back in England on 4 September 1843. He was awarded the Grande Médaille d'Or des Explorations

The Grande Médaille d’Or des Explorations et Voyages de Découverte (Great Gold Medal of Exploration and Journeys of Discovery) has been awarded since 1829 by the Société de Géographie of France for journeys whose outcomes have enhanced geog ...

in 1843, knighted in 1844, and elected to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1848.

Search for Franklin's lost expedition

On 31 January 1848, Ross was sent on one of three expeditions to find John Franklin. Franklin's second in command was Ross's close friend Francis Crozier. The other expeditions sent to find Franklin were the Rae–Richardson Arctic expedition and the expedition aboard HMS ''Plover'' and through the Bering Strait. He was given command of , accompanied by . Because of heavy ice in Baffin Bay he only reached the northeast tip of Somerset Island where he was frozen in at

On 31 January 1848, Ross was sent on one of three expeditions to find John Franklin. Franklin's second in command was Ross's close friend Francis Crozier. The other expeditions sent to find Franklin were the Rae–Richardson Arctic expedition and the expedition aboard HMS ''Plover'' and through the Bering Strait. He was given command of , accompanied by . Because of heavy ice in Baffin Bay he only reached the northeast tip of Somerset Island where he was frozen in at Port Leopold

The locality Port Leopold is an abandoned trading post in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It faces Prince Regent Inlet at the northeast tip of Somerset Island.

Elwin Bay is to the south, while Prince Leopold Island is to the north.

...

. In the spring, he and Leopold McClintock

Sir Francis Leopold McClintock (8 July 1819 – 17 November 1907) was an Irish explorer in the British Royal Navy, known for his discoveries in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. He confirmed explorer John Rae's controversial report gather ...

explored the west coast of the island by sledge. He recognized Peel Sound

Peel Sound is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk, Nunavut, Canada. It separates Somerset Island on the east from Prince of Wales Island on the west. To the north it opens onto Parry Channel while its southern end merges with Franklin Strai ...

but thought it too ice-choked for Franklin to have used it. In fact, Franklin had used it in 1846 when the extent of sea ice had been atypically low. The next summer he tried to reach Wellington Channel

The Wellington Channel () (not to be confused with Wellington Strait) is a natural waterway through the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut. It runs north–south, separating Cornwallis Island and Devon Island. Quee ...

but was blocked by ice and returned to England. Ultimately every member of Franklin's expedition perished.

Personal life

Ross married Ann Coulman in 1843. A blue plaque marks Ross's home in Eliot Place,

Ross married Ann Coulman in 1843. A blue plaque marks Ross's home in Eliot Place, Blackheath, London

Blackheath is an area in Southeast London, straddling the border of the Royal Borough of Greenwich and the London Borough of Lewisham. It is located northeast of Lewisham, south of Greenwich, London, Greenwich and southeast of Charing Cross, ...

. His closest friend was Francis Crozier, with whom he sailed many times.

He also lived in the ancient House of the Abbots of St. Albans in Buckinghamshire. In the gardens of the Abbey there is a lake with two islands, named after the ships ''Terror'' and ''Erebus''.

Ross remained an officer in the Royal Navy for the rest of his life and was subsequently promoted several times, his final rank being Rear-Admiral of the Red awarded in August 1861.

Ross died at Aston Abbotts

Aston Abbotts or Aston Abbots is a village and civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England. It is about north of Aylesbury and south-west of Wing. The parish includes the hamlet of Burston and had a population of 426 at the 2021 Census.

Manor

"A ...

on 3 April 1862, five years after his wife. They are buried together in the parish churchyard of St. James the Great.

In fiction

Ross, played by British actor Richard Sutton, is a secondary character in the 2018 AMC television series ''The Terror'', portrayed in a fictionalised version of his 1848 search forFranklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sect ...

, as well as in the 2007 Dan Simmons

Dan Simmons (born April 4, 1948) is an American science fiction and horror writer. He is the author of the Hyperion Cantos and the Ilium/Olympos cycles, among other works which span the science fiction, horror, and fantasy genres, sometimes wi ...

novel on which the series is based. Ross is also mentioned continually by Jules Verne in his novel ''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras

''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'' (french: Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras) is an adventure novel by Jules Verne in two parts: ''The English at the North Pole'' (french: Les Anglais au pôle nord) and ''The Desert of Ice'' (french ...

'' (for example, chapter XXV is entitled 'One of James Ross's foxes').

Tributes

* TheRoss seal

The Ross seal (''Ommatophoca rossii'') is a true seal (family Phocidae) with a range confined entirely to the pack ice of Antarctica. It is the only species of the genus ''Ommatophoca''. First described during the Ross expedition in 1841, it is ...

, one of the four Antarctic phocids

The earless seals, phocids or true seals are one of the three main groups of mammals within the seal lineage, Pinnipedia. All true seals are members of the family Phocidae (). They are sometimes called crawling seals to distinguish them from t ...

, first described during the Ross expedition

* The James Ross Strait

James Ross Strait, an arm of the Arctic Ocean, is a channel between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula in the Canadian territory of Nunavut.

long, and to wide, it connects M'Clintock Channel to the Rae Strait to the south. Isla ...

, Ross Bay, Ross Point, and Rossøya

Rossøya, sometimes referred to as Ross Island in English, is an island located in the Arctic Ocean. It is a part of Sjuøyane, a group of islands in the Svalbard archipelago, some 20 km north of the coast of Nordaustlandet, Svalbard in A ...

in the Arctic are all named after him

* , former name of ''Noosfera'', a National Antarctic Scientific Center of Ukraine

The National Antarctic Scientific Center (NANC) ( uk, Національний антарктичний науковий центр, abbreviated as НАНЦ) is an organization of the Ukraine, Ukrainian government, part of the Ministry of Education ...

research ship.

* The crater Ross on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

is named after him

* Ross's gull

Ross's gull (''Rhodostethia rosea'') is a small gull, the only species in its genus, although it has been suggested it should be moved to the genus '' Hydrocoloeus'', which otherwise only includes the little gull.

This bird is named after the Br ...

, a small gull, the only species in its genus, that breeds in the high arctic of northernmost North America and northeast Siberia

* Ross Dependency

The Ross Dependency is a region of Antarctica defined by a sector originating at the South Pole, passing along longitudes 160° east to 150° west, and terminating at latitude 60° south. It is claimed by New Zealand, a claim accepted only b ...

, Ross Island, Ross Ice Shelf1) ertrand, Kenneth John, et al, ed.The Geographical Names of Antarctica. Special Publication No. 86. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Board on Geographical Names, May 1947. 2) ertrand, Kenneth J. and Fred G. Alberts Gazetteer No. 14. Geographic Names of Antarctica. Washington: US Government Printing Office, January 1956. and Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

in the Antarctic are all named after him

* Mont Ross, the highest mountain, at a height of , in the Kerguelen Islands

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the sub-Antarctic constituting one of the two exposed parts of the Kerguelen Plateau, a large ...

, is named after Ross

See also

*European and American voyages of scientific exploration

The era of European and American voyages of scientific exploration followed the Age of Discovery and were inspired by a new confidence in science and reason that arose in the Age of Enlightenment. Maritime expeditions in the Age of Discovery were ...

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ross, James Clark Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars 19th-century explorers 1800 births 1862 deaths Anglo-Scots English people of Scottish descent English polar explorers People from the London Borough of Islington Explorers of Antarctica Explorers of the Arctic Fellows of the Linnean Society of London Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Royal Navy rear admirals Military personnel from London